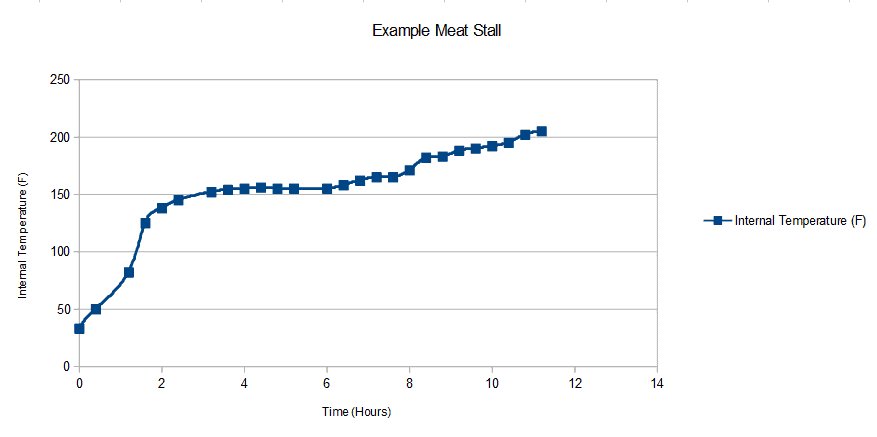

Why Brisket Stalls (Stops Increasing in Temperature)

This phenomenon is essentially “porous bed free expansion cooling” or evaporative cooling.

You can think of this like when People sweat – we do so to cool our bodies down.

However, when the humidity is high outside, sweat evaporation slows down, meaning it feels hotter.

That’s why they say it’s not the temperature, it’s the humidity that gets you.

As the temperature of the cold meat continues to rise, the evaporation rate increases until the cooling effect balances out the heat input.

The meat then plateaus until all the moisture on the surface is gone.

This is a super important realization because most of the bark formation occurs after the stall.

Yet, most articles, videos, recipes, etc. will tell you to wrap during or even before this happens.

So they’re compromising bark to cook the meat faster.

What Temperature Does it Stall at?

At around 150-165F.

But I don’t think you should wrap at this temperature.

In my opinion, this is bad advice because you miss out on creating a better bark – which on a slice of brisket is only a small thin strip.

I’d suggest waiting till around 170-180F in the thickest part of the flat (shown below).

Probing Brisket While it’s Stalling

When you go to probe a brisket you’ll get 3 different temperatures.

Flat muscle temperature:

Thickest part of the flat:

Point temperature:

To summarize:

- Flat: 167F

- Middle: 175F

- Point: 184F

The point will almost always finish faster than the flat. The front of the flat will also take longer to finish than the rest of the brisket.

The thickest part of the flat is usually the best measure of when to wrap as it’s a middle ground between the two muscles.

By waiting till 175-180F to wrap, you also create a better bark.

4 Main Ways to Beat the Stall

- Wrap in a full foil wrap

- Wrap in butcher paper

- Wrap in a foil boat

- Wait it out

The method you use will be based on your personal preference, but to summarize:

- A full foil wrap will trap more moisture and soften the bark more, but will come to tenderness the fastest.

- Butcher paper is porous meaning it will trap less humidity. Meaning the bark becomes less soggy.

- A foil boat exposes the fat cap throughout the cook and renders the fat better. The bark is more crunchy.

- Unwrapped meat takes the longest to come to tenderness and may even dry out.

For brisket, I like to foil boat.

Here’s my recipe for this but below is a summarized guide.

I wait till 170-180F in the thickest part of the flat.

I put the brisket fat side up in the foil, crumple the foil around the meat and then finish it in my electric smoker set to 250F until the thickest part of the flat is 190F.

From there I drop my electric smoker to 175F, cover the foil boat with foil so it’s completely wrapped and then hold the meat overnight.

The meat has less of a chance to dry out, is supremely tender, and the fat cap is slightly softened but still crunchy.

2 comments

Paul

Good advice! I waited to wrap at 175-180 and the brisket cooked just fine through the stall point. The bark was good. Thank you!

Dylan Clay

Happy to help Paul!