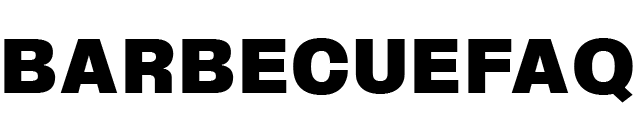

Brisket bark is the exterior crust or pellicle (skin) that forms on meat.

It is a result of chemical reactions:

- The Maillard reaction.

- Polymerization that results in the pellicle.

The bark is often considered to be the best part of the brisket.

Jump to Sections of this Article:

- The Rub You Use and Why Pepper is Important

- The Effects of Hardwood Smoke on Meat

- When to Wrap and Why You Should Wait Longer

- Your Smoker and its Airflow and Why Huge Offset Smokers have an Advantage

Your Rub Can Matter (It’s All About Pepper!)

Likely the single most important ingredient for forming a crust on brisket is coarse black pepper.

That’s why almost every commercial brisket rub includes a coarse ground version (typically 16 mesh).

Here’s a couple popular options:

If you need 16 mesh black pepper, this is the one I use – it’s 14-16 mesh.

While this type of pepper is rather pungent out of the bottle, during the long smoking process, this pungency is lost.

As the fat starts to render the pepper locks into the fat and is held there.

Salt penetrates into the meat and the rest of the rub ingredients sit on the surface.

The pepper becomes part of the bark and forms a “crust.”

Peppercorns are also a darker hue meaning the color of the bark is darker from the get go.

A Quick Note on Sugar:

A lot of resources like to say that the sugars will “caramelize” which causes the browning. However, table sugar won’t start to caramelize until temperatures of around 320F.

If you’re smoking low and slow (225-275F), how can these sugars caramelize?

They can’t – the browning is from maillard reactions.

Activated Charcoal is a Cheat for Color

A lot of rubs like to use “activated charcoal” to help with this dark color.

However, the “bark” that gets created is almost a “faux bark” on brisket.

This is the same reason most Pork rubs use lots of low-grade paprika – you get that red color from the get go.

Even looking at the examples of someone using a rub with this ingredient – the surface often looks dry, almost matte black.

As apposed to real bark that’s a glossy velvet black on its own; This bark is a result of smoke.

The activated charcoal serves absolutely no purpose other than cheating color.

Granted, if you don’t have a smoker and just have an oven – these rubs can be good options.

Personally, I’d rather get crust from pepper and color from smoke rather than a tasteless ingredient like food-grade activated charcoal.

Smoke Changes the Color and Texture of Brisket

If you were to cook a cut of meat without smoke, it would turn a dark mahogany color; This happens due to things like oxidation and maillard reactions.

When you introduce smoke you get a black velvety sheen over time.

To illustrate:

The brisket below had very little pepper in the rub, but it’s still a deep mahogany color due to maillard reactions.

This is after 5/6 hours of smoking:

3-4+ Hours later, a deep black sheen:

The exterior is also dry, yet shiny; The surface is jerky-like, forming a pellicle or skin on the exterior.

This pellicle helps create a textural difference in the mouth that’s appetizing.

STOP Wrapping so Early

A lot of articles/recipes on the internet for brisket will tell you to wrap brisket at 150-165F.

The reason for doing this is because this is the temperature a brisket will start to stall at.

The stall is essentially just the brisket sweating moisture, which cools the meat down.

The biggest reason wrapping during this process is bad advice is because most of the bark formation occurs after the stall – as I’ve attempted to demonstrate above.

By wrapping you effectively trap steam and soften any sort of bark that you might of formed.

If you wrap during this process, you’re essentially just trapping moisture to speed cook time and your brisket will lack any sort of meaningful bark.

Dylan’s Suggestion: Wait until around 170-180F to wrap your brisket.

Airflow is Overlooked In Terms of Pellicle Formation

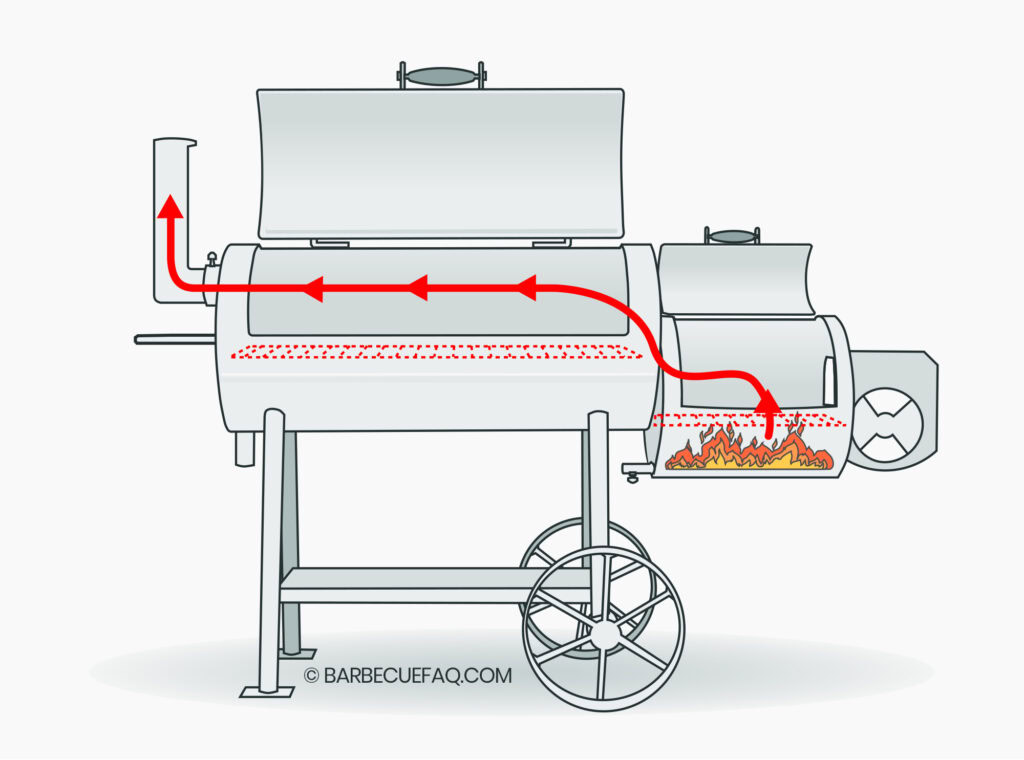

The convective current in your smoker also has an impact on bark.

BBQ Joints typically use large offset smokers featuring 500 – 1000 gallon drums.

These smokers have a very strong convective current (similar to the picture below) that is pulled over the top of the brisket.

This airflow helps to dry out of the surface of the meat as much as possible.

Hence why I mentioned that you should wrap later into the stall.

Bark formation occurs as a result of this moisture drying out and happens after the stall.

Now, regular folks don’t have 500-1000 gallon pits.

We have things like:

- Pellet cookers

- Charcoal grills

- Drum smokers

- Electric smokers

- Kitchen oven

- etc.

The airflow in any of these devices isn’t even close in comparison to these pits.

Meaning, surface evaporation and the ensuing bark formation also isn’t as substantial; Albeit, still possible.