Most know that chicken is considered safe to eat at 165F.

BUT dark meat like thighs should be pushed well past 165F into the territory of 200F.

Doing so allows the collagen and connective tissue to break down and render into a gelatin.

Unlike breast meat, chicken thighs will still remain moist and juicy and the meat pulls away from the bone.

The skin fat is also rendered far better leading to crispy, crackly skin.

Chicken Thighs and Collagen Content

Chicken thighs contain far more collagen than breast meat.

Collagen is a protein that’s found in bones, skin, cartilage, and muscles; It’s also an essential component of connective tissue.

In a case study by Chen Y, Qiao Y, Xiao Y, et al. – we can see that regardless of chicken breed, total collagen content in thigh meat was always greater.

They also note that “tenderness of meat was negatively correlated with collagen content.”

aka thighs are less tender than breast.

Rendering Collagen is a Function of Time & Temperature

From Douglas Baldwin’s article on Sous Vide cooking, we can see that the lowest possible temperature for collagen conversion is 131F.

He also goes onto say that the higher the temperatures, the faster the denaturing of collagen.

BUT, simply searing a chicken thigh to 200F won’t automatically render collagen.

You need to have both time and temperature.

The goal is to get the chicken thigh above 160-200F+ and to keep it there for an extended period of time – without burning the chicken.

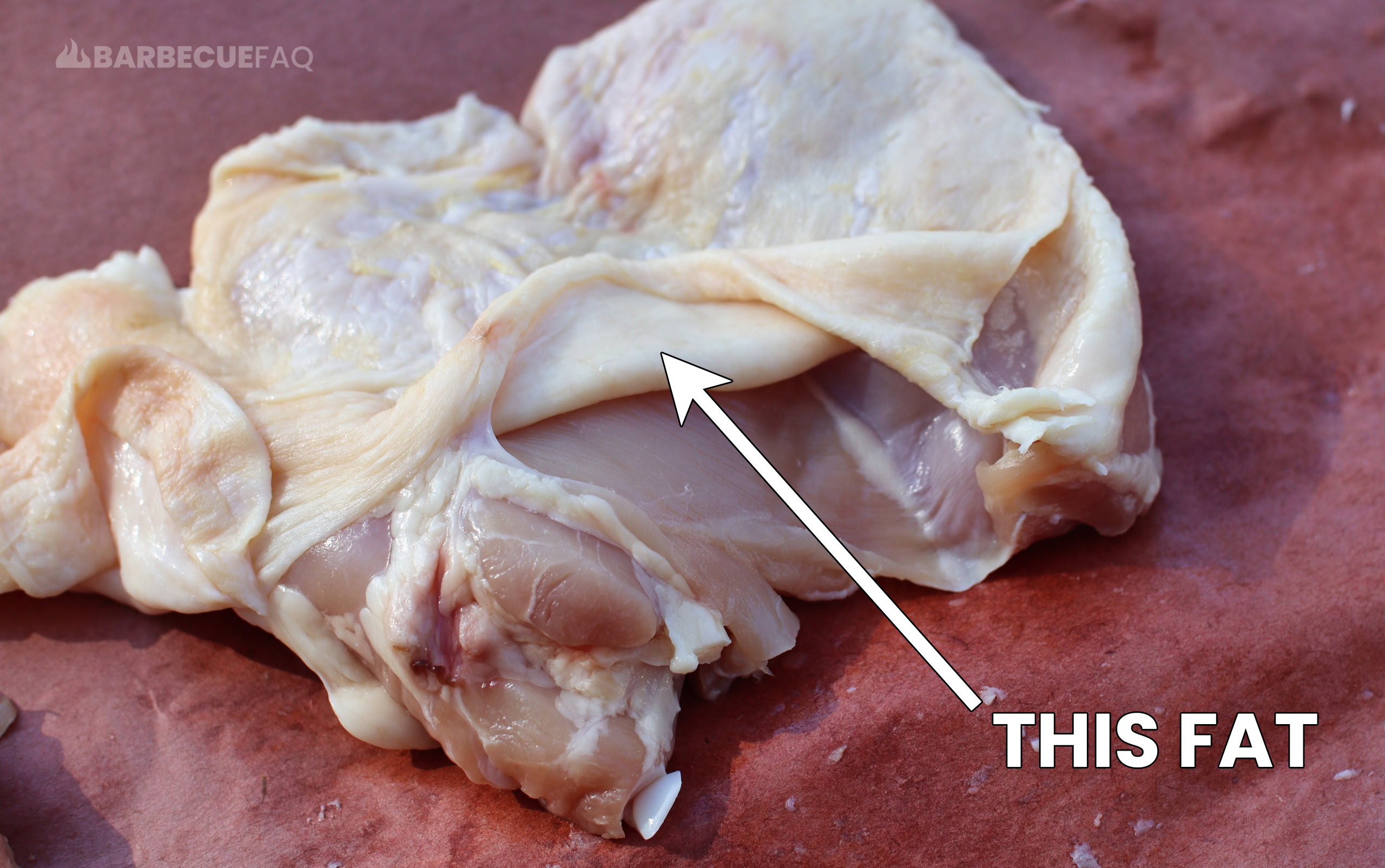

Skin Fat is ANOTHER Reason Your Chicken Skin is Rubbery

Chicken skin is composed of around 55% water, 35% connective tissue (most of which is collagen), 5-10% fat and 0.5% ash.

By cooking the chicken thighs to higher internal temperatures, you give more time for the skin fat to render under the skin.

Here’s an example with a chicken thigh at 165F:

There is still SO MUCH fat that can be rendered here.

Compared to a chicken thigh at 203F (below) that’s crispy, crunchy and crackly.

I’ll take option 2 every. single. time.

This thigh was also cooked over direct heat but kept under 325F so it didn’t burn.