When smoking food you want to achieve “thin blue smoke.” This color of smoke implies that the burning of the wood is efficient.

TBS is a thermochemical process called pyrolysis.

In this state, the chemical compounds that comprise the wood break-down into combustible gases – these gases result in desirable aromas and taste sensations that can attach themselves to your food.

Where-as “Thick white smoke” is essentially inefficient combustion and results in acids and gases that aren’t palatable; Namely wood creosote which is bitter.

Wood Science Explained

Hardwoods used for smoking meat are primarily made up of 3 organic compounds:

- Cellulose

- Hemicellulose

- Lignin

The cellulose and hemicellulose make up the structural material of the wood, where-as lignin holds them together.

Cellulose and hemicellulose are chains of glucose (sugar).

When burned they effectively caramelize and are responsible for most of the color components as well as the sweet, flowery, and fruity aromas.

The breakdown of Lignin creates phenolics (aromatic compounds) that create distinct elements like smokiness and spiciness (syringol and guaiacol).

- Syringol is responsible for the smokey aroma.

- Guaiacol is responsible for the smokey taste.

This is the reason why Mesquite wood has a pungent smokey flavor. It has far more lingin content than say hickory.

Thick White Smoke (TWS) or “Dirty Smoke”

This section is based on personal experience and what I’ve found after smoking meat for roughly a decade.

Keep in mind, barbecue is a centered experience and what I like, you may not.

The reason thick white smoke is considered “bad” or “dirty” is because it implies incomplete combustion (gas particles that are left un-burned).

Prolonged exposure results in an acrid taste from ash and creosote. The particles are also much larger and will readily adhere to wet surfaces (meat).

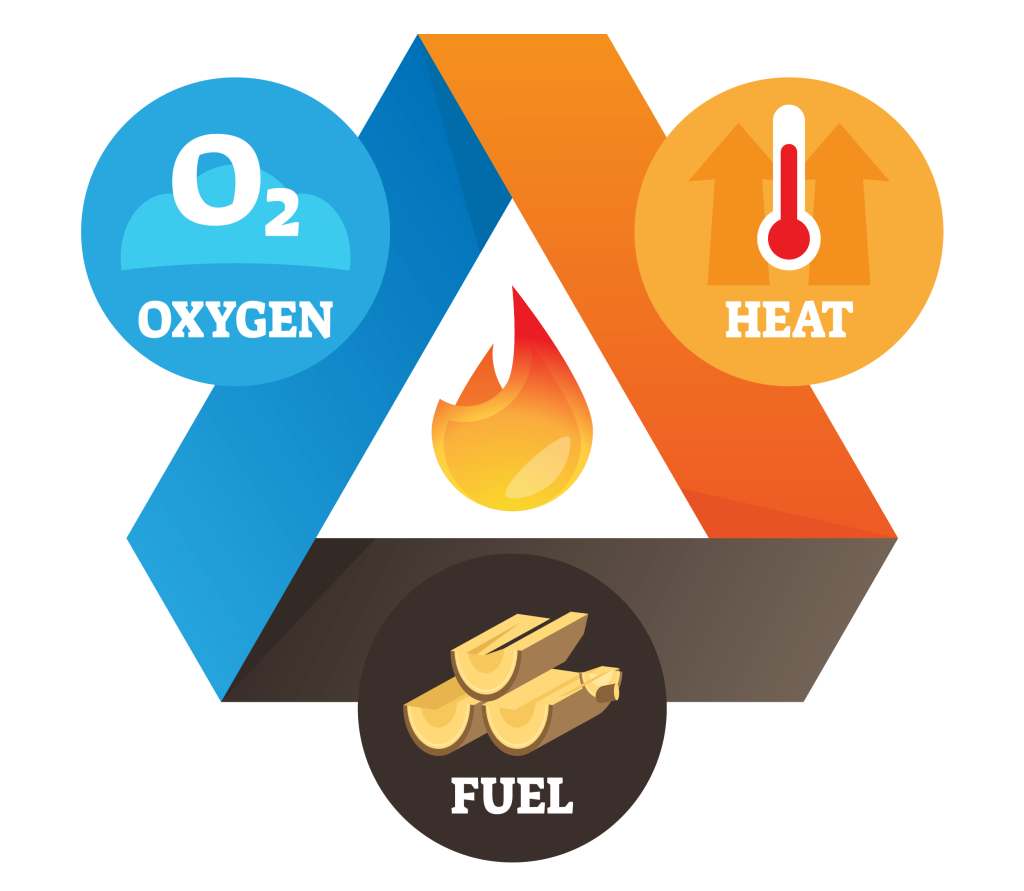

There are 3 things necessary to produce smoke:

- Oxygen

- Combustible fuel

- Fire/heat source

When all of these elements are introduced, combustion occurs; This is how the “fire triangle” works.

In order for smoke to be produced the heat and oxygen can be adjusted so that the combustible material will smolder rather than burning resulting in visible smoke.

Remember, most of the flavor components come from the gases, not the smoke.

The composition of the gases depend on oxygen and temperature.

The following temperatures and observations are from Dr. Greg Blonder’s research on this topic:

- Below 450F: The material combusting is primarily hemicellulose. Releasing acids and gases that aren’t palatable.

- 500F: At this temperature, most of the hemicellulose has burned or turned into charcoal. Cellulose releases water, acids, alcohols, tars and combustible gases. These components also aren’t very palatable, however they’re responsible for meat’s mahogany color (cellulose is a sugar polymer).

- 600F: At this temperature the number of cellulose compounds decline.

- 650F-750F: The acids, tars, and bitter components (above) are minimized while Lignin/smoky taste and aroma are maximized (desirables).

- 800F: Potential for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) to form which are carcinogenic. The desirable components are also destroyed.

We can see from the above that a lower temperature fire (450F) creates an acrid bitter taste.

High temperature fire also destroys the desirables.

Meaning the sweet spot is 650-750F.

This is the biggest reason some people opt to smoke hot and fast (275+) as apposed to low and slow (225).

On many smokers, smoking at 225 requires you to dampen the oxygen which starves the fire and results in incomplete combustion and the non-desirables, namely wood creosote.

I’ve found this to be true too and tend to go with 250F-ish.

This is Also Why Offset Smokers Have an Advantage

Since the firebox is offset from the rest of the smoke chamber – you can burn a hot clean fire.

In the case of some people who use Mesquite, the “smoke” may be entirely clear.

With say a Charcoal Grill, it’s quite hard to burn a hot fire because you risk burning your food since it’s so close to your fire.

I like to add a water pan because it’s a heat sink and lets you burn a hotter, cleaner fire. Although you’ll burn through far more charcoal this way.

It also works to deflect heat away from the meat.

Don’t Get Confused by Moisture Content in the Wood

Virtually all wood will emit white/grey smoke during the initial phases of combustion as moisture is being released.

Wood is hygroscopic meaning it will lose/gain moisture depending on the humidity and ambient temperature. Seasoned hardwoods used for smoking typically have a >20% moisture content.

If you’re using a water pan, the water also releases steam that you may confuse for white smoke – as it appears whitish.

After 20 minutes, if your smoker still has billowing clouds of white smoke, you likely have a problem with the wood being used or the airflow/oxygen – prolonged exposure will likely result in a more acrid or bitter flavor.

The keyword here is prolonged.

In my experience, if you’re cooking hot and fast (300+), white smoke works perfectly fine for burgers, steak, chicken, even ribs.

But smoking with white smoke for 10+ hours is going to create acrid/bitter flavors.