By Dylan Clay

The ideal thickness for a steak is between 1 – 2 inches; With 1.5 inches being the most common “best” thickness you’ll see quoted.

However, something that some people fail to understand is that some cuts of “steak” can’t get this thick – it’s just not genetically possible; Good examples include skirt steak or flat iron steak.

Steak thickness is based on the beef primal you’re working with and consumer preference; Simply put, Butcher’s cut what sells and that often includes the thickness of beef steaks.

A lot of resources will boldly state: “Thicker steak is better.”

I’d wager to say that’s true, to a point.

The reason I say this is because as you make a steak thicker, you need to employ different methods of cooking in order to cook it optimally; This is primarily due to internal temperature and crust formation.

This is also why 1.5 inches is what most folks deem the sweet spot.

You can build a thick crust – that’s not too thick – and you can dial in your internal temperature quite easily.

To help understand what I mean by the above in regards to thickness and internal temperature, we can look at the ribeye steak and the prime rib roast.

Some quick bullet-points:

Even though these cuts come from the same location, they’re typically cooked much differently as a result of their thickness.

With prime rib, People will use one of two methods:

In this case, when the prime rib is served you’ll have a slice with uniform doneness across the entire cut – usually in the spectrum of rare to medium-rare.

This slow roasting period can take several hours until the desired internal temperature is reached.

With Ribeye steak, it’s possible to achieve the Prime-rib style of doneness (wall-to-wall color) via methods like Sous vide or the Reverse sear. However, in my opinion, you miss out on creating a superior crust.

I prefer to sear my steaks in my cast iron skillet.

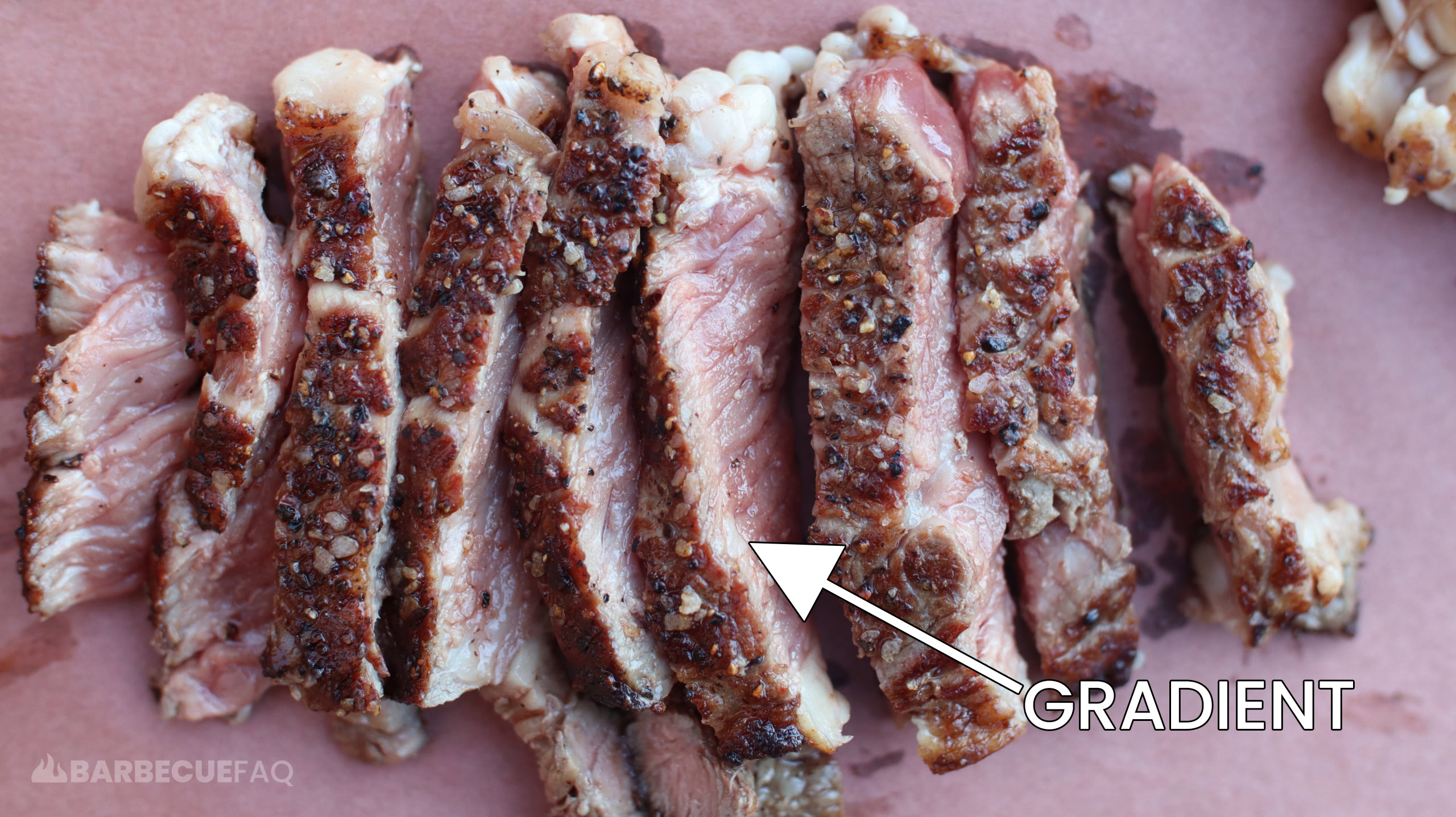

Steak that’s pan seared achieves a superior exterior crust, followed by a pronounced gradient of finishing temperatures, and juiciness in the steak.

By “gradient” I’m referring to the fact that pan searing creates an exterior, crunchy, dehydrated crust, followed by a small band of well-done meat, that slowly grades into a measured internal temperature – like medium-rare.

Pictured below.

However, as you get thicker – say 3+ inches – the issue is, how do you maintain your crust while still reaching your target internal temperature?

Here’s the crust on a 2 inch steak:

The 2 inch thick steak has a thicker, more dehydrated crust – notice the intermuscular fat is also rendered better.

Steaks thicker than 2 inches will also have larger gradients of doneness, which is less appetizing.

Likely the layers will be:

Truth be told, the goal when forming crust on steak is to get the steak as dark/brown as possible without burning the oil or the meat.

When oils reach their smoke point they’ll release free radicals as well as a substance called acrolein – which gives burnt food an acrid flavor and aroma.

Meaning, you’re better off slow roasting “steaks” this thick.

The reason I keep putting the word steak in bold, or italics, or in quotes is because these larger/thicker cuts would more optimally be called roasts. Hence why I brought up Prime Rib Roast and Ribeye Steak in the first place.

Similarly, if the steak is cut too thin, it can be hard to create crust without overcooking the meat (more on this below).

The word “steak” is sort of a catch-all term that people use to refer to any number of cuts from a cow.

For example, when fabricating rib steaks, a butcher has complete control over how thick the steaks can be simply because the rib primal is a huge muscle; They can be thick, thin, bone-in, boneless, etc.

Pictured above I showed a 2 inch ribeye, here’s a 1 inch ribeye:

However, some muscles like skirt steak or flank steak, can’t get thicker than 1/2 – 1 inch thick; It’s just not genetically possible. The same could be said for a few other cuts of steak.

Thin cuts of steak include:

Due to being thin, these cuts of steak work better when you take a different approach to cooking.

To illustrate:

In most cases cuts like skirt, flank, and bavette are marinated for 24-48 hours because their loose grain structure takes well to marinades.

After marinating 24-48 hours, these steaks are typically cooked over high heat for short periods of time. The goal being to create a sear/crust while maintaining juiciness or free moisture (cooking to rare or medium-rare).

These thin cuts of steak are then sliced against the grain to tenderize the individual slices. Doing so shortens these fiber lengths making it easier for your mouth to chew.

In this case, the marinade adds tremendous flavor, we’re also cooking to rare/medium rare to maintain juiciness, and we’re then cutting against the grain to further tenderize the cut for eating.

Due to what we talked about above, the crust on these steaks is less substantial simply because the steak is thin.

Meaning, we lose out on developing the extent of flavor and texture that you can on thick cuts of steak simply because we’re restricted by the smaller thermal center.